So my record Twisted City is 10 years old. Fancy that. Here's a little mini-documentary about how it was made and what it's about: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1l8n9RLLcdg

David Bowie EP

David Bowie EP by Five Grand Stereo

A very quick note to say that December 18 sees my band's 'David Bowie' EP released and available on all major streaming platforms.

You can find out more about the David Bowie EP here.

You can read a piece on the making of David Bowie’s ‘Hunky Dory’ album on the Five Grand Stereo website too.

Aaaaah. It's the Bee Gees. Being murdered.

Had band members Michael Kirkland and Ben Woollacott round to do some recording yesterday. We had a lot of fun putting down three part harmonies on a few tracks for the new album. I guess we thought we were being the Beatles on 'Because' or The Beach Boys on 'Pet Sounds' but listening back like we were being more like the Bee Gees really, only sans medallions and sexy outfits and being murdered.

You can watch the quite amusing results here. First you hear the ungodly sound of us singing alone at the start of the video, and then at the end you'll get to hear the track with all our ahem, bits put together.

Recording keyboard parts with Michael Kirkland

Orla organ

Here is a clip from a new track I'm working on, This Stuff. Michael is playing my weird old keyboard from (I think) the early 80s. An 'Orla'. It makes a lot of farty noises but every now and then you can coax something rather nice out of it.

Anyhoo, enjoy - video below.

Why the chart success of 'Ding Dong! the Witch is Dead' is so significant

Margaret Thatcher

There's something rather sneaky going on in Britain at the moment: an attempt to cod the population into believing that its most controversial, divisive prime minister ever was a unifying figure that everybody supported (or should have supported) and whose policies “saved the nation.”

An array of tactics are being employed to convince us that Thatcher was essentially a Churchill Mark II: the state-funeral-on-the-sly; the recall of parliament; a torrent of newspaper headlines pronouncing her Britain's greatest ever PM; vast numbers of Thatcherite talking heads queuing up to commend her legacy to pliant TV news anchors; and, of course, a royal presence at her funeral. It’s nearly as bad as when we had to endure months of catching buses sporting huge pictures of Maggie’s hairdo photoshopped onto Meryl Streep’s head.

However slickly presented, however, the messages about Thatcher being put about by her cheerleaders are at odds with reality.

She was not unifying; I doubt that more vitriol has been directed at any other post-war British prime minister (even Bush-loving, Iraq-bombing Blair), dead or alive.

She was not universally popular: she won her elections with a smaller share of the vote than all previous post-war Tory prime ministers, and at every general election she contested, around 60% of the country was consistently voting for other, mainly left-liberal, parties (her electoral success had much to do with a split left and the UK's questionable voting system).

As for her policies – both the ones she implemented in office and the ones she influenced afterwards – you will find many who will line up to question the merits of privatising such basic utilities as water, transport and energy, and plenty of economists see her 1986 'big bang' financial market deregulation (and the subsequent adoption of Thatchernomics by New Labour) as laying the foundations for the financial crisis that is doing all our heads, wallets and spare bedrooms in today.

Despite all this, it is unlikely that from listening to politicians, watching TV or reading your preferred daily rag you will get any real sense of the fact that in truth, a huge tranche (majority?) of the UK population disapproved of what Maggie did to her country, and that she was not just disliked but hated by millions.

You also won’t find many journalists lingering that long on her support for murdering despots like Pinochet; or her backing of the apartheid regime in South Africa. Yet in our supposed age of austerity, no expense is being spared by an otherwise penny-pinching state to ensure that this woman goes down in history as a secular, unifying saint; and no effort is being spared by the, ahem, impartial media we enjoy in the UK in ramming this sainthood down our throats.

Against this backdrop of enforced-Thatcher-respecting, the rise of Judy Garland's Ding Dong! the Witch is Dead up the charts may seem trite or tasteless, but it is actually very significant.

Yes, it is rather rude – and, perhaps, a touch sexist – to compare the UK’s first ever female prime minister to a witch. Yes, it disrespects the dead (and, some would argue, witches). But however crude this musical protest might appear, as the track has approached the top of the charts, it has become a pointed countermelody to an overplayed tune which insists that Margaret Thatcher was the saviour of the nation. It sticks two fingers up, in a nicely British (and, appropriately, collective) way, to the notion that Thatcher was a unifying figure and a force for good.

The many British people who view Thatcher in a negative light do not have £10m handy to organise elaborate ceremonial events designed to make a political point. They can't recall parliament at public expense to reminisce on their experience of Maggie. They don’t control the airwaves. They don’t happen to run newspapers. They can’t rely on a royal showing up at an anti-Thatcher party (not even a Z-list one, like Princess Michael of Kent). But delightfully, they’ve still managed to find a way to forcefully question the Thatcher myth being sold to them.

With its lyrics referencing lullaby leagues, lollipop guilds and munchkins, the chart success of Ding Dong! may feel like a somewhat childish, minor victory, but it’s actually hugely important, because it forces a largely Thatcher-supporting media to report on a widespread and deeply-felt unhappiness with Thatcherism; and crucially, the success of the song can’t simply be dismissed as being the work of just a few troublesome crusties from North London (despite my own best efforts in cajoling my friends to buy my music, there just aren’t enough of these types to propel you into the charts).

Introducing Lettie

Lettie

I sometimes do a bit of music promo work for a lovely music PR firm full of lovely people called Prescription PR.

Whilst doing so, one particular Prescription client caught my ear, the very talented Lettie. Her music didn't just appeal to me though - The Irish Times, Bloomberg, MSN, the Press Association and a truckload of other publications were blown away, and Cafe Nero liked her song 'Mister Lighter' so much that they playlisted it in all their UK stores. Absolute Radio and Radio 2 have been spinning her tracks too.

Anyway I got chatting to Lettie and she has kindly agreed to do a set to open my forthcoming London gig on 17 October at The Wilmington Arms - another reason to come along :)

To find out a little bit more about Lettie, I'd suggest watching some of her quirky videos at http://www.lettiemusic.com/film.html and reading Tony Clayton Lea's Irish Times review.

Upcoming gigs in London and Poland

A quick note about a couple of upcoming gigs - I'm playing a shows in London, UK and in Rzeszów, Poland soon. As ever it would be wonderful to have your support - gig details below (I'll be following this post up with a note about who the special guests are too).

17 October 2012 - London, The Wilmington Arms

A full-band show at London's Wilmington Arms venue on Rosebery Avenue. Tickets are limited so please buy in advance here. Tickets are £9 when bought in advance online or £10 on the door.

- The show starts at 8pm.

- The venue address is 69 Rosebery Avenue Clerkenwell, City of London EC1R 4RL.

- The nearest tube is Angel (a ten minute walk away) or alternatively catch a 19, 38 or 341 bus.

20 October 2012, Rzeszów, University of Rzeszów

A full-band show in Poland at the University of Rzeszów - Sala Koncertowa Instytutu Muzyki Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego, ul. Dąbrowskiego 83.

Doors at 6pm. For ticket reservations, please call +48 17 8721214 (9am - 12pm)

You can purchase tickets in advance at the booking office located at Uniwersytet Rzeszowski, Instytut Filologii Angielskiej, al. Rejtana 16b (building A3), room 112 (9am-12pm)

Tickets are 30zl each.

The music industry is alive and well - and being financed by the musicians

Two Door Cinema Club's 'Beacon' album

So Two Door Cinema Club’s album has leaked. The band’s singer Alex Trimble has written fans a message about this, and, like David Lowery’s recent rant at an intern regarding the topic of illegal downloading, it’s been doing the rounds online. I much prefer Trimble’s more gentle, thoughtful (and pleaful) take on the situation than Lowery’s; but regardless of tone, both pieces add to the sense of a music industry in deep crisis and a bunch of suffering musicians getting ripped off by their listeners.

However I’ve got a hunch that the music industry’s probably doing fine…and, in a sense, probably generating as much, if not more, dosh than ever before.

I think of the music industry as something different to the record industry. The record industry – individuals and companies manufacturing and selling records – is generally screwed, because the digital revolution has led to a situation where recorded music has been reduced to a set of ridiculously-easy-to-copy files. However, the same digital revolution has also led to an enormous explosion in the number of bands that are actually in a position to record, distribute and promote music; this means that the music industry – which I think of as all the people, products and services generating revenue as a result of music-making, not just CDs and MP3s – has a much bigger customer base than ever before. This customer base is not the music-purchasing public though – it’s the musicians who, in most cases, are no longer the people generating income from music, but the people financing this industry.

There have always been thousands of bands all over the world that have wanted to make records. However, until about a decade ago, when advances in technology started to put ridiculously good recording equipment in the hands of musicians, release-quality recorded music was expensive to produce and very difficult to distribute, meaning that only bands with a significant budget (those who were signed or had investors) generally got to put out records. However, these days, every Tom, Dick and Harry has an album up their sleeve, because they a) simply bought a laptop and an audio interface and recorded it on that, or b) availed of studio time that is now much cheaper than it used to be (due to studios having to compete with the aforementioned laptop and audio interface). As for distribution, getting an album into the ears of a (theoretically) global audience is now incredibly cheap and easy thanks to the likes of iTunes, Spotify and so on.

What does this mean? A huge increase in the number of bands releasing albums. However, most bands – understandably – are reluctant to pour their hearts and souls into recording an opus only for it to only ever be played by their mums. So they start to buy services that might give the album a chance to reach the great unwashed. Graphic design. Manufacture. Photography. Web design. Web hosting. E-newsletter design. Public relations. Radio pluggers. Printing of posters. Distribution of posters. Online advertising. Digital distribution. Venue hire. Smoke machine. Hairy sound guy…the list goes on. Generally speaking, all the above services come with a price tag, and thanks to the explosion in the number of bands releasing music independently, a big “DIY-release” market has developed as a result, packed full of companies, consultants and freelancers catering to the 'needs' of the DIY musician (not to mention a whole load of pro-audio equipment vendors selling gear that promises to make your record sound like it was recorded at Abbey Road).

And here is where the opportunity for musicians to get ripped off really lies. For the vast majority of self-releasing musicians, the whole ‘some bastard downloaded my album for free’ argument is a bit of a sideshow. (In fact, independent musicians are generally delighted when somebody downloads their album illegally, because it hints at the fact that somebody somewhere actually likes their music). No, the opportunity to get properly robbed arrives when bands start to purchase the ‘DIY-release’ style services I mentioned earlier.

The problem is – and I speak from personal experience here – that bands are not like normal customers of goods and services. For most musicians – certainly those without children – their music is their baby. They don’t think rationally about it. They love it so much that they are prepared to spend whatever it takes (or whatever they have) to help it succeed in that big bad music-filled world out there. They ignore the fact that people are not buying music in the droves that they used to, and that there are probably more artists flogging music than ever before. The idea of a return on an investment doesn’t figure in their thinking at all, and many artists releasing albums now don’t have any management, meaning there is nobody in the background to say ‘whoa, don’t spend all that cash on putting together a triple disc limited edition vinyl press of your concept album about beans’.

This generally results in musicians making four big mistakes:

They don't set a strict-enough budget or consider the fact that they need to actually sell X number of records to make their money back

They don’t shop around for the best deals on the things they do need (if they actually know, of course, what these things are)

They invest in things they absolutely don’t need (over-the-top packaging; posters; narcotics for the A&Rs who are unlikely to attend the launch party anyway)

They hire unscrupulous, snake-oil-salesmen who operate out of a glorified shed in a field north of London promising fame and fortune to artists in the form of a £1,500 per month ‘reputation management’ arrangement

I’ve made many of these mistakes in my time; but in hindsight I don’t think I would have made them had I grasped the importance of the ‘record industry’ / ‘music industry’ distinction I discussed earlier. If musicians understand that the record industry is dying on its arse, and that the notion of people paying for recordings is becoming increasingly quaint (whatever we feel about the moral implications of that), it forces them to think more creatively about how to monetise their music rather than simply hoping millions of people will buy their next album. And if artists understand that the ‘music industry’ is increasingly about servicing a market of DIY-musicians with products and services that may or may not result in album sales, it might encourage them to think in a more business-like way, decide what actually might generate a return on an investment, work with the right people or agencies and crucially, avoid the snake-oil salesmen – or at the very least, ask some probing questions about the snake oil.

Saxophones in the studio

A lot of instruments, including some fairly obscure ones, have ended up on my recordings. But one instrument that hasn't (somewhat surprisingly) is the saxophone. So imagine my delight when it turns out that my good friend and fellow Hackney-ite Michael Kirkland turns out to be a very soulful sax player. Had to have him round to blow some notes all over some of my new stuff.

Do take a listen at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V9SgzrQUW_M (or if you're via player below).

Free music: why David Lowery's letter to Emily White has totally missed the point

David Lowery

Recently musician David Lowery wrote an article on The Trichordist blog where he took a young NPR intern, Emily White, to task for admitting in a blog post that she and her peers didn’t really pay for music in this new-fangled digital era.

In a passionate, much-talked-about but ultimately rather over-the-top open letter addressed to her he made the argument that people who did not pay for music were behaving immorally and causing a social injustice; in fact, he went so far as to imply that people who downloaded music for free were guilty of causing the deaths of rock stars.

His thoughts went viral and no doubt many of my musician and producer friends clearly sympathised with them, as when I logged into Facebook I found that around 20 musical chums had posted a link to his article. I understand their motives; however – and speaking as a musician myself – I have to take issue with the original blog post.

There are so many things wrong with Lowery’s article and his arguments that it’s hard to know where to start, but let’s begin with economics. When supply outstrips demand, generally speaking prices fall. And when supply seriously outstrips demand, prices approach zero. Which is what has happened with music – there is simply no scarcity of it any more, for two reasons: one, and like it or not, music is now available on millions (billions?) of computers in incredibly easily-to-copy files as opposed to in exclusively physical formats, and two, the revolution in home and project-studio recording means that there has been a huge explosion in the number of recordings available.

It doesn’t matter what either Lowery or indeed the ‘adherents of Free Culture’ that he refers to think of the ethics of this situation, the reality of it is that there are just more songs available now – and in incredibly easy-to-avail of formats – than there are people who want to listen to them, with all the inevitable implications this has for the cost and purchasing of music. It’s astonishing that Lowery, who has been teaching music undergraduates about the economics of the music business for the past two years, has not grasped this obvious point (or simply tries to wish it away).

Secondly, throughout his whole article, Lowery ignores something even more obvious: digital revolution or no, the vast majority of musicians have never made much (if any) money out of their art. Let’s go back to 1997, when the Spice Girls were big and, more to the point, before file-sharing had really got off the ground. If you made an album then, you would probably have had to pay a substantial amount of money to record it (it was before the days of 128-track digital multitrackers in every bedroom); you would then have encountered high manufacturing costs (I remember paying £150 to manufacture 10 CDs in 1998); finally, you would have had to work out how on earth you were going to distribute and promote your opus.

The upshot? It cost you a truckload of money to make an album; a truckload of money to manufacture it; and after all that you probably wouldn’t have been able to sell it in any meaningful quantities at all, due to shelf space in record shops being so difficult to attain and advertising costs being prohibitive. What did this mean? Any independent musician daft enough to make a record in the 90s would end up selling 5 copies of his album and incurring huge debt.

Contrast that with today. Thanks to inexpensive computers and audio gear, recording is so cheap, it’s practically free; manufacturing is, in the digital realm at least, also free (it doesn’t cost anything to generate an MP3 version of a track); and digital distribution via the likes of iTunes, Amazon and Spotify, is, surprise surprise, more or less free as well.

Throw in the potential of (free) social media, email, digital ‘fan-funding’ and cheap online advertising and, if you play your musical cards right, you could actually end up making money from a record that you made for next to nothing. Or, at the very least, generating a decent fanbase that might in the future lead to some sort of income, via live performances, merchandise or other gimmicks.

Extremely few musicians will ‘make it’ to the extent that they’ll make a shedload of cash, but that’s always been the case; and at least the current situation means that more musicians than ever before will experience the joy of establishing a fanbase that extends beyond their mum and dad (and it’s worth noting that, believe it or not, some musicians are in it for the listeners rather than the money; if the internet doesn’t provide the latter, it certainly provides the former).

It would have been nice if Lowery had mentioned some of these upsides provided by the digital revolution, or pointed out that musicians now get a whole lot of incredible stuff for free themselves that would have been filed under ‘pipe dream’ in the past (free recording, free manufacturing, free distribution and arguably some free marketing are not to be sniffed at). And you don’t hear Lowery argue, for example, that by opting for the free, ‘self-recording’ approach, musicians have put a lot of recording studios out of business, or caused the deaths of record producers (as somebody who self-produces a hell of a lot of my music, I sincerely hope that I have not inadvertently killed anyone).

Another thing that Lowery is very quiet about in his article is the fact that musicians are by no means the only group that are affected by the digital revolution or the advent of ‘free culture’. The fact is, if you are creating anything that can be turned into a file – be that a news article, a book, a piece of software, a video game or a film – you are presented with exactly the same vexing question that faces musicians: how the hell do I make money out of this content in a context where file-sharing is ubiquitous?

Lowery completely fails to answer this question in any meaningful way – or to mention that despite the prevalence of file-sharing and free music there are actually still plenty of ways of monetising music. There are film-sync deals; publishing deals; revenue generated in various ways from advertising; live appearances; merchandise; digital Radiohead-style ‘honesty boxes’; royalties from airplay; and royalties from Youtube video plays.

If that’s not enough, it’s important to remember that the profit margins on music that is sold online can be much, much higher than in the ‘good old days’ that Lowery seems to hanker after (particularly where direct sales from websites are concerned). Ok, so you might be selling less music, but what if you are making £6 per album download from your own site, compared to £2 from a CD sold in a HMV store?

This is not to say that making money out of music is in any way easy, but I repeat: it never has been. Getting a successful music project off the ground has always required a whole load of things – I’d like to think that it all comes down to great tunes, but hard work, good hair, good luck, and knowing a bunch of hip journalists are probably far more important.

Throughout rock history, or indeed before anyone recorded any music all, musicians have always complained about how hard it is to make a buck from their art – and Lowery’s blog post, despite its current popularity with many musicians, is just the 21st century (dare I say internet) incarnation of that. It clearly struck a chord with a cash-strapped musical community; but I suspect that the wiser members of that community will see it for what it was – a rock star venting frustration at a lack of sales by first patronising, then picking on, an unsuspecting young intern. It might make him and some other musos feel good for a few minutes, but it probably won’t help him – or the aforementioned musos – make any more money.

Besides all that, I'd love to know if, in his youth, David Lowery ever copied a mate's copy of an album onto one of those quaint blank cassette thingys.

New mini-documentary about Twisted City

I've gone all 'Behind The Music' and put together a little video about the making of Twisted City. This is maybe a little self-indulgent, as I can't say Q or Mojo regularly include it in their top 100 albums of all time, but I know that there is a little band of Twisted-City lovers out there, and this video is for them. It's got commentary about the recording of the album, tracks, and photos that I haven't put online before. Plus a truckload of bad haircuts.

The video can be watched at http://www.youtube.com/embed/1l8n9RLLcdg

Trumpets!

This video diary experiment I'm doing with the recording sessions for my new album continues...I recently had a very talented trumpeter (and recipient of a 5 star Guardian review for his most recent album) called Andre Canniere around recently, to put down some brass on a track called Anyone Can Be a Star. We tracked him about 16 times, playing exactly the same parts, and we ended up with a pretty beefy trumpet solo.

You can take a look at us recording said trumpets here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RNK0GCXq2k

Enjoy...

Recording a gospel choir - with one singer

I've been working with an excellent singer called John Gibbons now for a number of years; he's incredible. I had him round to record some backing vocals for some new tracks the other day, and as part of this whole video diary thing I'm making, I shot some footage.

As you'll see from the video below, John is a one-man gospel choir, and a great one at that.

You can take a look at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9cfhB5Qm3iE - enjoy.

New music, featuring Jane Fraser

Jane Fraser

As part of the recording process for album number 3 (which is going slowly, but pretty well), I've started recording with a singer from Limerick called Jane Fraser. She's got a fantastic voice and you can check out some of the takes we did recently in the latest installment of the video diary I'm making of the recording sessions - either below, or at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MaNmV0ohaw4

Enjoy.

Videos from the new album recording sessions

A quick note to let you know that I'm starting to put together some little video clips from the recording sessions for my new album. They let you see what we're getting up to and give you a sneak preview of the new record. You can view the first of these below.

Enjoy.

Computer says no: time to fear the algorithm?

Hal

When you are waiting at a red traffic light at a junction, a little algorithm – a formula or set of steps for solving a particular problem – is silently judging you. It’s working out how long you and other motorists have been waiting at the various sets of lights at the junction, how many pedestrians have pushed a button at a crossing, which road is the most important one, what time of day it is, how quickly you need to pee and so on.

Based on these variables and what the algorithm makes of them all, you’ll either be waiting a short or a long time before you can stop cursing, uncross your legs, release the handbrake and move on (assuming, of course, that you’re the sort of person who uses the handbrake. There is a very good reason for using a handbrake whilst waiting at the lights, but that’s another, and perhaps rather boring, blog post).

Algorithms are in the news a lot at the moment, partly because a clever chap called Eli Pariser has written a book called The Filter Bubble about them. Annoyingly, this is a particular interest of mine, and he’s beaten me to writing a tome about it – but in my defence I’m a new dad and finding the time to write a blog post is very tricky, let alone attempting a book. For similar dad-related reasons, I haven’t got round to reading The Filter Bubble, but from what I can gather from reviews and an interesting TED talk he gave recently, Parisier’s focus is on how algorithms are used online.

More on that in a moment, but first it’s worth pointing out that algorithms are nothing new – they’ve been around for donkey’s years, and are as much an offline phenomenon as an online one. Healthcare professionals use detailed algorithms to examine symptoms and establish courses of treatment; call centres use them to evaluate your response to certain questions and ascertain what crap to sell you. If you’ve got a Volvo it will probably tell you off for starting the engine without putting your seatbelt on, and if you get in an elevator, it will hopefully take you to a floor which corresponds to the button you press. In their simplest form, algorithms are little flowcharts which ‘process’ a situation – or you. If yes, do this; if no, do that.

All the above examples seem rather mundane – and unless you’re particularly into the electronics in a Volvo, they are. But lately, algorithms have taken on a new importance. As with most things, the internet has sort of ‘turbo-charged’ them: it’s made them (a) more sophisticated and (b) far more prevalent, to the point where it’s virtually impossible to do anything online without encountering an algorithm that is doing its very best to make you take a very particular course of action.

You are probably only reading this blog post because Facebook or Google used an algorithm to process you – or your search query – in a very specific way and decided that this article was for you.

If you’re reading this in the south of France, you may well be there because when you perused the Ryanair site, it did some sums and thought that offering you a so-called free flight to Nice was a good idea.

If you’re staying in a four star hotel in Nice you may be there because when you searched for hotels in the area, an online advertising algorithm pointed you in the direction of a cheap deal on four star hotels in France. (Personally, if I was in a four star hotel by the Mediterranean, I wouldn’t be reading a blog post about algorithms, I’d be doing something more interesting, but there you go.)

Algorithms helping you get cheap flights seems pretty harmless; a good thing, right? Perhaps, depending on what you make of global warming. However, online algorithms are not just benign little bits of code that help you find stuff you like; they are often rather more sneaky than that.

If you use Gmail to read your emails, Google’s algorithms are reading them too, and displaying adverts to you based on the things – however sensitive or confidential – you are discussing in the mail.

If on Facebook you casually mention that you are a bloke and list yourself as ‘single’ (yes, I know, as if anyone ever does that casually), you will see a plethora of attractive big-breasted ladies beside your news feed, all enticing you to visit their dating website, where of course all the ladies are as attractive and big-breasted as the girls in the ads. Not that I would know.

If you visit an insurance website, a series of algorithms will track your every click and change the content of pages in real time to ensure that you only see the policies you are most likely to buy.

If you search for a product on eBay, an algorithm will take note of this, put a ‘cookie’ on your computer (without asking you), and you will see a shedload of adverts for that product when you visit other, completely different websites. This is perhaps why, when I turn on my computer after my partner has been on Ebay, I see countless adverts for Cath Kidson products wherever I go online, and if I’ve been using her laptop, all she will see is guitars.

This is all about personalisation: very big, powerful companies filtering content and showing you stuff based on who they think you are. (And to be fair, they’ve got a pretty good idea. Every time you clicked that little ‘like’ button on Facebook, you told it you are into Ann Summers products, Tom Jones and Pizza Hut. Hence the constant ads for sexy Welsh pizza).

It’s not because these companies particularly want to make the web experience better for you – although sometimes, this is a side-effect – they really just want to sell you something. But either way, personalisation algorithms are now being employed on an industrial scale, to the point where to use the internet is to be pushed hard, and in a sophisticated way, in a certain direction. And the interesting – perhaps disturbing thing – is the effect this is having on our worldview and behaviour.

Let’s take a look at worldview: it will come as no surprise to anyone who reads my blog, or has the misfortune to be subjected to my Facebook status updates, that I’m an outspoken pinko-lefty-liberal type. But I’m a tolerant guy, and I have some conservative friends. However, I’m unlikely to ‘like’ their status updates about so-called benefit scroungers or click on links they post to Daily Mail articles.

Equally, my conservative friends probably won’t be too keen on my rude status updates about David Cameron or the links to Guardian editorials that I post. However, I am quite likely to click on other people’s left-leaning posts, and my Tory cousins will no doubt hit ‘like’ every time somebody whinges about a mythical gold-plated public sector pension, calls for the return of the death penalty or wants to privatise the NHS.

These kind of social interactions have consequences for Facebook users. This is because the network makes use of an algorithm called ‘Edgerank’ to determine what to display in users’ news feeds. Without going into too much detail, it takes three variables – ‘affinity’, ‘weight’ and ‘time’ – to make a call on what pieces of content are relevant to each Facebook user. With the examples highlighted above, it will conclude that ‘right-wing’ posts are less relevant to me, and that ‘left-wing’ posts are less relevant to my conservative chums. And it will edit them out of our respective news feeds. This is truly a shame, as it means I can’t wind up my conservative friends any more. Rather more importantly, a valuable exchange of ideas is no longer taking place. Despite all the sharing of information and views that Facebook was meant to bring, every time I use it, a piece of maths is effectively hiding content from me. Not just me: 500 million or so Facebook users who are looking to it for information 20 times a day, 365 days a year. And the overwhelming majority of these have no idea at all that Facebook is taking such an active role in deciding what they should see. I’m no social scientist, but I’m sure this kind of filtering of content applied on such a huge scale cannot but have a significant impact on how people see the world.

This algorithmic, personalised filtering is not restricted to social media news feeds. It’s now crept into search results. Up until fairly recently, you could be fairly confident that if both you and your friend searched for Russian brides on Google, and you both lived in the UK, you’d get exactly the same results. However, about a year and a half ago I started noticing – not, I must stress, as a result of searching for Russian brides – that when I searched for the same thing on Google, but in different contexts, that the results were very different. By different contexts I mean searching for the same thing

- on more than one computer

- when I was logged into my Google account, or when I was not logged into my Google account

- after clicking a particular search result

- in a different geographical location.

This was a bit of a headache, as at the time I was doing a bit of freelance work involving search engine optimisation for a music site and I kept getting multiple sets of results for the exact same keywords. It turns out that Google had started doing the same thing as Facebook – looking at a whole load of variables relating to me and making assumptions as to what floated my boat, rather than giving me an impartial set of links. In his TED talk, Parisier highlights this filtering extremely effectively, by describing an experiment where he asked a few of his friends to google ‘Egypt’ and send him a screenshot of the results provided by Google. The screenshots all varied enormously – Google had personalised the search results to the nth degree for each of his friends.

It’s worth noting however, that personalisation isn’t restricted entirely to online algorithms written by big powerful corporations; in a sense, we also write our own. Here’s an example of how. These days I mainly read the news on a smartphone. I'm going to come across as very bien-pensant here, and perhaps a bit of a knob, but my two news sources of choice are the BBC and The Guardian – and I "consume" (eughh) news via two apps that I’ve downloaded for my phone. Both these apps let me select exactly what content I want to appear when I open them. So, when I’m reading the news, I’m presented with content to do with politics, comment, technology, music and whatnot – and generally speaking not much fashion, showbiz and sport. But when I used to buy a newspaper, I would read it from start to finish, meaning I was invariably exposed to – and would read – a much wider range of stories. With news apps, even though they don’t use any surreptitious personalisation filters, they subtly encourage users to apply their own personalisation filter. The upshot is arguably a narrower view of what’s going on, despite there generally being more content available to browse.

So should we be worried about all this filtering that’s going on? Yes. Because it means that the internet is changing in a profound way. Traditionally the web has been (justifiably) viewed as a tool that

- widens access to information

- provides an ‘impartial’ way of sifting through information

- increases transparency.

But now, the two major prisms through which people see the online world – arguably Facebook and Google – are throwing the above notions out the window. Facebook is actively restricting what people see in news feeds, based on perceived taste. Google’s results are no longer impartial – they’re personalised. And both services have not been at all transparent about how this filtering is / has been applied, or how to switch personalisation off.

And that’s just Facebook and Google – a multitude of sites are going down the personalisation route. It’s the Next Big Thing on the web. And when it gets to the point that every site you visit is running an algorithm that shows you ‘relevant’ information only after it has checked your IP address, cross-referenced its content with what you searched for on Google recently, examined your Facebook likes, scanned your computer for cookies and checked out that Russian brides website you were perusing the other day, the internet can no longer be considered a 'source' of information. It will be a gatekeeper far, far more powerful than Rupert Murdoch, and one that you can’t haul before parliament – or throw a foam pie at.

The end of the download is nigh

iPod

If internet rumours are to be believed, June 6 2011 may possibly be the music industry’s equivalent of “The Rapture” (for those of you who haven’t been on Facebook recently, or have been living in a hole in the New Forest, "The Rapture" was beginning of the end of the world, and was supposed to happen on May 21. Nothing of the sort happened, unless you are reading this on a cloud with Jesus or you are feeling rather hot and can’t concentrate on this article because a devilish imp is poking your bottom with a pitchfork). Of course “The Rapture” turned out to be a damp squib, but June 6 is more likely to live up to its reputation as being a day on which the music industry will change forever.

So what’s happening on June 6? Well, according to a multitude of newspaper articles and blog posts, it’s the date that Apple may unveil their ‘cloud service’ – a system that lets listeners stream music from the web. Now, as the cloud service in question hasn’t been unveiled yet, it’s not clear what form this is initially going to take. It could be that Apple are simply going to offer something similar to Amazon and Google’s new cloud systems, which allow you to upload and stream your music collection on the web, wherever you are.

But frankly, that’s a pretty boring approach, and unlikely to be what Apple’s “cloud offer” will be. If rumours are to believed, Apple have been working hard to secure licensing agreements with the “big four” record companies – Warner Music Group, Sony Music Group, EMI Group and Universal Music Group – which means all this is heading in one direction: a streaming service similar to Spotify’s, where listeners will eventually be able to stream whatever music they like (for a fee, of course).

If Apple does go down this route, it means that an en-masse switch from paid-for downloads to on-demand music streaming is now just around the corner – the rise of 3G web connections, increasing use of smartphones and Apple’s 75%-85% share of the download market would more or less guarantee that streaming becomes the de facto way that music is consumed. If Apple release a software update for iTunes containing streaming functionality, millions of iPod, iPhone and computer users in general all around the world would suddenly be able to stream music instead of paying to download files. The choice of tracks would be vast – significantly bigger than Spotify’s library, due to full music industry buy-in – and the reach of the service would be enormous too, thanks to Apple’s strong global position in both the download and mobile device markets. All this would arguably result in death of the download, and pretty quickly too.

What would be the impact of this on musicians? Well, for bands who are signed to a label and getting a significant marketing push, it would be fairly good news – it makes their music even easier to access. For musicians without a budget however, it would represent more of a headache. This is because streaming removes the attractiveness of a key tool used by musicians to entice people to sign up to email updates: the free download. For several years now, indie musicians with any clue whatsoever have been giving away downloads in exchange for the ability to communicate with fans online – with individual tracks, EPs or even albums being swapped for email addresses or Facebook ‘likes’. However, there is not much of an incentive for a potential fan to grab a free download from a band if a) they don’t really download music anymore and b) the track can be streamed anyway on iTunes.

The free-download-for-email-address scenario that we’ve seen over the past few years has led to a situation where clued-up independent musicians have, to a certain extent, been able to bypass traditional gatekeepers – labels, journalists, distributors, promoters and radio stations – yet still make quite respectable amounts of money from music via direct-to-fan sales. Perhaps it’s a negative way of looking at things, but with downloads diminished as an incentive for joining a mailing list, indie musicians will be able to communicate directly with fewer and fewer listeners online; so ironically, technological advancement may lead us back full circle to a situation whereby only those with serious budgets can introduce consumers to new music - and create any demand for it.

But if you are an indie musician who has built a business model on free downloads, and all this does sound like the end of the world, don’t despair yet. Pretty much every technological development in the music industry has shut one door only to open another; and with all these developments, the trick is to stay ahead of the curve. The musicians who twigged that free downloads helped build databases first built the biggest databases (and sold the most music and merchandise); and it will be the musicians who twig how best to use streaming cleverly who will monetise the new landscape. The trick is to think fast. But the end of the download is nigh – get ready.

The Alternative March for the Alternative

On Sunday, we stopped at some services just off the M1 where I bought a bottle of Sprite. Whilst paying for this overpriced but - due to a rather bad hangover - much needed fizzy liquid I took a quick glance at the shop's rack of Sunday papers.

Unsurprisingly, most of the front pages were covering the 'March for the Alternative', the anti-cuts protest which saw 250,000 or 500,000 people (depending on whether you believe the Police or the protest's organisers) march through Central London in protest against the very deep cuts to public services.

I was one of those protestors, and although I have a large beard at the moment, it is more by accident than design, so before you ask I am not a hippy, a trade union member, a communist, an anarchist or even in Red Ed's Labour Party. I will possibly own up to being a beardy weirdy, circa 1969-71, but that's probably more to do with taste in music than politics and the look I'm going for with my next record. Mainly I was there because like a lot of dudes, bearded or no, I'm quite fond of British public services.

Anyway, enough of the beard stuff. Where was I? Oh yes, in a service station, bottle of Sprite in hand, hungover and looking at examples of fine British journalism. I was expecting the papers to cover the march in a negative light - but I really wasn't expecting there to be quite such a disparity between what actually happened on Saturday and what was being reported. I and the other 249,999 or so peaceful protestors might as well have been on another march, on another planet; certainly not at the event that was being written about on the front pages of virtually every one of the respectable British newspapers I was looking at (if that's a correct way of describing them; last time I looked most British newspapers seemed to be owned by foreign, rich, eccentric tycoons, but that's another day's moan).

The event that the press was portraying was one of anarchy; violence; chaos; war. Yes, there was some violence, for which 149 people were charged. That is, on the Police figures, 0.06% of the total turnout, or, based on the organisers' figures, 0.03%. Either way it would appear that 99.94% to 99.97% of those protesting were not charged with any wrong-doing or violence. It was an overwhelmingly peaceful protest, and all of us aforementioned peaceful people were angry - in a peaceful way of course - that some idiots had disturbed our, well, peacefulness.

Maybe it was too much to expect that a paper of record, The Sunday Times, might make more of the fact that hundreds of thousands of British people from all walks of life came out to protest against their own government than that a profoundly small minority caused violence. Or that so-called 'quality broadsheets' would focus exclusively on 'carnage', 'battles', 'chaos', 'violence' and accompany these lurid descriptions with pictures of an unruly but entirely unrepresentative mob. What was being reported was not the 'March for the Alternative', but some weird 'Alternative March for the Alternative', completely at odds with reality.

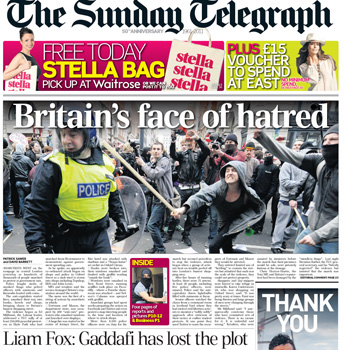

But whilst I was irritated by most of the coverage, one front page actually made me feel genuinely sad. The Sunday Telegraph had a huge picture of a policeman being attacked by some guy with a stick, accompanied by the headline 'Britain's Face of Hatred'.

This picture and headline instantly and deeply undermined up to half a million people, from all sections of British society, from all age groups and from all backgrounds, who had come together and marched not out of hatred but in support of an idea that is arguably the polar opposite of hatred: the idea that we are, to coin a phrase, 'all in this together'; that public services matter; that they transform lives for the better; and that they should not be slated, sacrificed and privatised because of the huge greed of the banking sector. Even if we who were marching in support of public services are profoundly misguided, and the controversial austerity measures are going to eventually solve all of Britain's economic problems, we were not remotely marching out of hate; we genuinely believe that public services are a force for good that make lives better for millions - and that every step should be taken to protect them and fund them properly. Idealistic, perhaps, but not hateful.

The Sunday Telegraph's front page will have been seen by countless other hungover guys in motorway services all across Britain. Or people popping to the corner shop for a pint of milk. And for millions this in-your-face, out-of-context image will give a lasting impression that the March for the Alternative was a march for hatred. But it's not how the event was, or what it was about.

I took another snap of the 'March for the Alternative'. It's unlikely to be seen on the front page of a newspaper; it will probably go no further than the little band of devoted and perhaps unfortunate readers who read my scribblings. But it's a picture which tells the story of the day in a much more honest way, and shows what it was about. You can take a look below.

The Long Tail

This year my holiday reading list wasn't very long - I was too busy on the beach trying to follow the UK election on my phone (a sign of the times, eh). Nonetheless I did get to read one book: 'The Long Tail' by Chris Anderson.

In this fascinating tome, Anderson highlights how in this new-fangled age of e-commerce, online retailers are actually making more money out of selling lots of individual niche products than they are from selling hits. The classic example given in the book is Amazon: in a given week they may sell thousands of copies of a particular Coldplay album, but during the same time they will sell far more albums by a variety of less-well known artists.

This creates the 'long tail effect', which is illustrated in the diagram below. On the left hand side of the graph you see the million-selling acts, seemingly way more popular than everybody else. On the right hand side you see the 'long tail' of all the other less popular niche artists that don’t sell as many copies of their albums. But because digital distribution has allowed literally anybody to sell albums online, there are now so many niche products available for sale that the tail goes on and on and on…until all the products that sell one or two copies a year actually generate more profit, when considered together, than the hits that might sell millions in a year. The little guys actually pack more of a sales punch.

This is great, obviously, for Amazon and other online retailers - all they have to do is stock as much stuff as possible. But what are the implications for all the niche artists - like yours truly? Well, to be honest, I don’t think the long tail effect helps niche artists that much in strict retailing terms. The best application of 'the tail' for generating music sales is probably to make as much of your music as possible available to buy – somebody’s going to want to buy that alternative nu-metal-emo-dance remix you did of some crappy B-side, so why not let them (the downside though is that putting ropey content out there may not be great for your artistic integrity or image).

However, what may help musicians a bit more is another long tail effect: the long tail of media. If you look again at the chart above, and this time think of the left-hand side of the graph as containing the big publications – national newspapers and magazines – and the right hand side of the chart as containing the bloggers (or online content creators), it becomes clear that the bloggers actually have a bigger readership than the traditional media. A country may have 10 national broadsheets, which will be read by millions of people a day, but millions of people in that country will be creating content on blogs or social networks every day which is read by 10 or more people a day.

Needless to say it’s fantastic for bands if they can get into conventional print publications – as this is brilliant for profile and will no doubt also influence what bloggers are writing about – but it’s bloody hard. In the absence of success in that area, the long tail of media points to an alternative strategy for musicians who need exposure. This is to convince a critical mass of bloggers and other content creators to advocate their music. This is not by any means an easy process – it requires a lot of targeted approaches, and a lot of email-writing, but if done properly, at least it offers some exposure instead of none. The digital revolution has created a situation whereby decent bands who had no hope of getting national press can now at least get their music written about and crucially, heard by a potentially large audience.

Of course, this probably fuels the creation of demand for niche music - and helps Amazon sell more of it. So perhaps the biggest lesson of all this is that if you're in a band you should probably give up now and go work for Amazon!

More Chris Singleton content

Pink Floyd put their foot down

I love Pink Floyd. My favourite album of all time is their masterpiece, Dark Side of the Moon. It is a stunning piece of work. And now, thanks to a legal victory by the band over their record company, EMI, I’m not going to be able to download individual tracks from it (or indeed any other Pink Floyd album).

Pink Floyd started this legal fight in order to “preserve the artistic integrity of the albums”. In their view, this artistic integrity would have been fundamentally undermined had listeners been able to listen to tracks out of context from the original albums by downloading them individually.

Now, I sort of understand this reasoning. The album format is a wonderful thing, and Pink Floyd have some wonderful albums, where each track is a component part of a whole; tells part of a story; segues ingeniously into another song; and so on. When it works, it works beautifully, and it makes for a great listening experience where the album, in its entirety, really is the piece of art and the songs are the component parts. So to a degree, I buy the argument that by allowing users to pick and choose tracks to download, the album gets lost or forgotten about. Which, when this happens, is of course a great shame.

However, I still think this is a bad move by the band, mainly because it will serve to significantly reduce the reach of their music – and the likelihood of people hearing their albums (and enjoying the aforementioned artistic integrity) in the first place. My bet is that a 16-year-old who is curious about and new to Pink Floyd might take a punt on a track or two if they were downloadable from iTunes – but is far less likely to take the plunge and buy a whole album without sampling their music first. Thinking back to the way I got into Pink Floyd as a youngster, it was entirely the result of hearing individual tracks out of context from the albums: I’d go round to mates’ houses where I’d hear mix tapes featuring Pink Floyd songs that were plonked alongside an eclectic mix of other stuff. I would never have bought a copy of The Dark Side of the Moon at all had it not been for those random encounters with Money or Time sitting uneasily next to Kinky Afro on an old cassette.

But regardless of whether the band’s legal win reduces the reach of their music, it leaves Pink Floyd in a position where they are odds with reality: legally they can control how people listen to their music, but in a practical sense, they can’t. This isn’t just about the MP3 era: since the cassette came along and home-taping took off in the 70s, listeners have had lot of control over how to listen to songs – in context, out of context, legally, illegally, whatever. Then the CD player arrived, and with it the ability to program song sequences or just hit ‘skip’ to rush past fillers on albums or hear good songs again. And if we’re honest about it, even the good old vinyl LP let you do that anyway, if you were prepared to physically look for the gaps in the grooves and slap the needle down on the song you wanted to hear. I certainly remember doing that when it came to some of the less-interesting Pink Floyd albums.

The download age has only reinforced this level of control: people may be forced to download Pink Floyd albums in their entirety now, but they will be downloading them onto technology which actively encourages out-of-context listening. Shuffle modes and playlist creation in my view, render the whole idea of artists prescribing how people should hear their music completely redundant. As an artist myself I’m not entirely comfortable with that, but it is a fact, and no amount of litigation can prevent this new-found listener control.

For me, however, the most persuasive argument against the ‘you-must-listen-to-our-albums-in-their-entirety stance’ comes from Pink Floyd themselves: if they are so insistent that every song must be heard in context, then why did they release no fewer than six compilation albums containing a mix of tracks taken from a whole bunch of different albums (some, like Money, even re-recorded especially for one compilation)?

If you don’t eat your meat, you can’t have your pudding.